We have become what we hate and it's not that bad

2026-01-01 18:55

Getting promoted in a regular job requires bribing your superior regularly. Your superior also does it so you are aware that this pyramid works as a cutthroat incentive scheme where salaries are redistributed upwards. At the main international airports the immigration lines are so long that plainclothes police officers offer you an informal fast track service for about 15-20€. The parliament, which directly administers the capital, has passed a unanimous resolution restricting the circulation of combustion engine vehicles within its inner ring road. There is one single company that builds electric cars, factories, residences and entire neighbourhoods. At the time of this writing, the capital has been filled with free electric buses that ferry people around the city. They are very practical, but they also take care of connecting neighbourhoods of said company with each other.

If this sounds like a capitalist dystopia from an American movie from the 90s, or a Korean movie from the 2010s, You are almost correct.

Welcome to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Vietnam is often presented as the place where communism won. Where David beats Goliath. Where the West had to come to terms with colonialism. This is the narrative of both the US and North Vietnam, and it’s been conveniently crafted, on the American side, to justify an involvement in a war that wasn’t theirs – they thought they were fighting communists, they ended up fighting Vietnamese people – and on the North Vietnamese side, as it helped push their agenda to the whole population

Their agenda, though, was not a communist agenda, it was a nationalist one. And in 2025, with one single company owning a huge part of the country’s infrastructure like it’s some real world version of the plot of Cyberpunk 2077, we can see that this is not a “corruption of communism”, but a continuation of the Viet Minh’s initial agenda: the ends justify the means, we use a peasant revolution to make Vietnam Vietnamese. That is the end goal.

How we got to this stage is quite twisted and it’s ungrateful to the (just) anti-colonial cause to assume that a capitalist dystopia was in their minds all along in the 1940s, but let’s take a chance to cut the bullshit and get rid of our ideological hangover and look at a bit of history.

Obligatory skippable section about “how we got here” that starts ridiculously early in time

Peninsular South East Asia is the place that is formally defined as “where German 20 year olds go backpacking, plus Burma”. It’s a very diverse land but local power struggles, colonialism and nationalism turned this relatively small area dense with tens of language groups and religions into a simplified set of two kingdoms, two communist countries, and Burma1.

Before the 50s the area was much more simple, as there were, in the whole region, only three “items” bordering China: England, France, and the Kingdom of Siam2. Burma and Thailand in particular were bitter enemies and the British colonisation was a gift from the heavens for Thailand as their main regional enemy got neutralised. The northern borders were way too annoying for conflict, and, conveniently, to the east lay two very weak kingdoms, which fell to the French quite easily.

To the east of those kingdoms lay the ashes of the Nguyen dynasty, the other regional bully turned subservient colonial state, a place that was referred to with many names, but now we all call Vietnam.

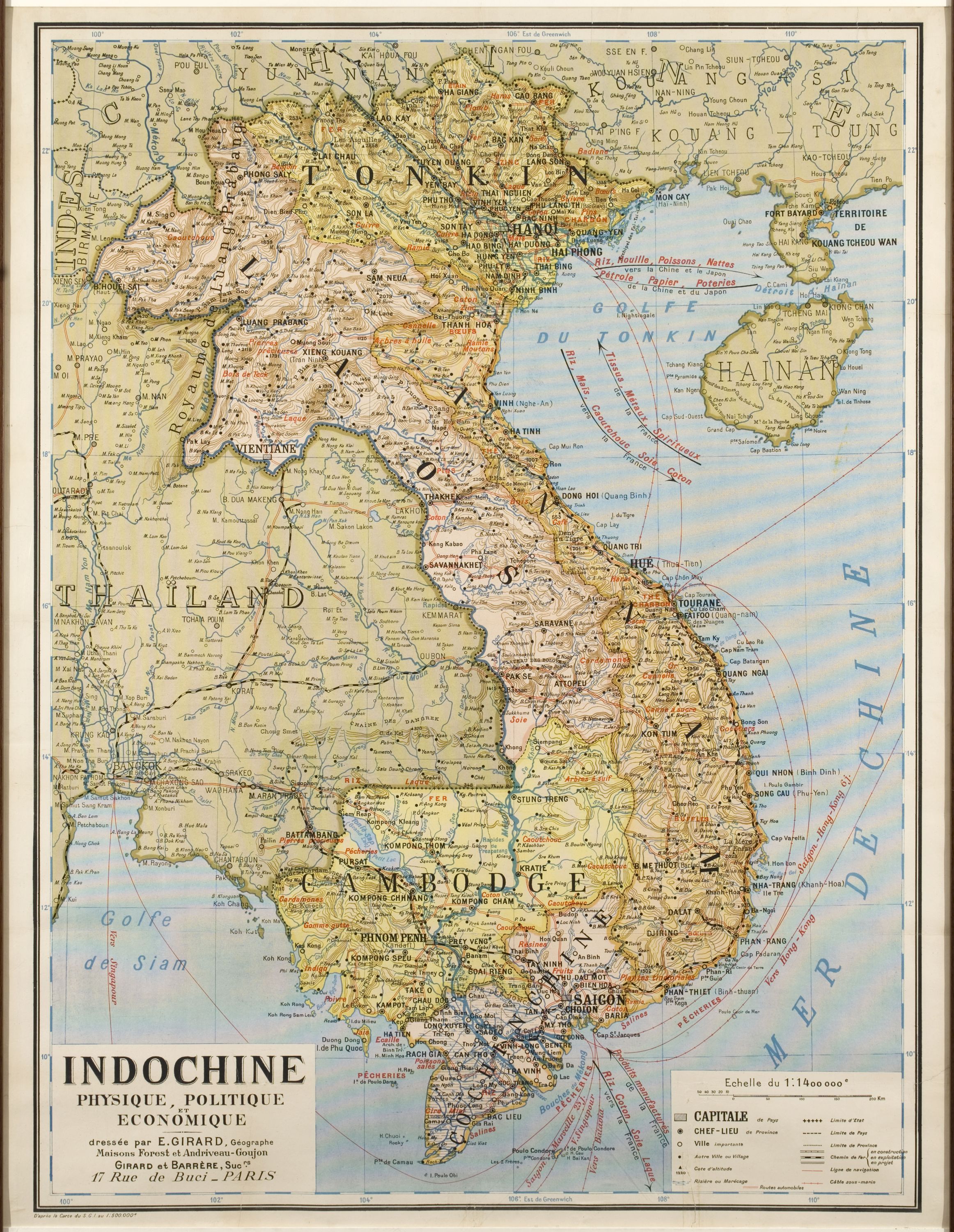

In the map above we can notice a few things. The first one is that Cambodia looks visually smaller than it is nowadays, and it is: Battambang and surrounding areas were ceded to France in 1907. A similar fate befell to parts of southern Laos. But perhaps more interestingly, what we now call Vietnam is split in three parts: Tonkin, Annam and Cochinchina.

Wait what, no Vietnam?

“Vietnam” until the Nguyen dynasty wasn’t a real nation-state, it was “the thing that goes from the Red river delta to the Mekong delta, along the coast”. It wasn’t united by flag or language. In particular, “the Vietnamese” were mostly settled in the northern part, broadly going from the Red River delta to what is now called “North-central Vietnam”, with Hue as its capital.

The South was something else. Until the 1400s there was one single Kingdom ruling all of it: Champa. Ironically, the borders of Champa were pretty much the same as the borders of the much later Republic of Vietnam (for friends and family, South Vietnam). The big exterminations following the defeat of Champa happened around the year 1500 but the cultural erasure was complete right after the final annexations of the last independent Champa cities in the 1800s by the Nguyen dynasty.

This all sounds boring and irrelevant but this process is what turned Vietnam into a culturally homogeneous region. Of the neighbouring states, only Cambodia shares this feature, but for Cambodia the “homogeneisation” process happened much, much earlier, and ironically it is the French that finished the job of settling the borders of Cambodia to “where Khmer people lived”, while Nguyen Vietnam did the opposite: it conquered the remaining areas of the region and turned them Vietnamese.

Not all kingdoms were equal

Laos and Cambodia have good memories of most of their kings, and in the case of Cambodia after a few decades of chaos the king returned and everyone lived happily ever after3.

In Vietnam there was a combination of factors at play. Maybe the freshly united kingdom felt threatening, or maybe, since the pot of nationalism started boiling around the world there was some fear this could spill over to Indochina and bring an end to the French colonial adventure in the region: the fear was justified since this is exactly what would happen later, and for this reason precisely. Regardless, France decided that while Laos and Cambodia could keep their cute little kingdoms, under their administration, Vietnam was too big to keep united, so it was split in three.

How the French got kicked out of Indochina

Splitting Vietnam in three was a terrible idea and this was probably obvious, given the region’s trajectory. But the fact that this almost trivial divide et impera strategy to decentralise power from Hanoi managed to, of all consequences, empower a rebel group from the most depressed part of the region, that was far from predictable.

The “middle” and Ho Chi Minh

Many places struggle defining what “their central part” is. Europe, Italy, Vietnam. Some places don’t even contemplate a “centre” (China, the US, Germany). The middle of Vietnam was always some sort of battlefield, first as the vague border between the Vietnamese kingdoms and Champa, then as the broad region of the Nguyen capital, Hue.

After the consolidation of Vietnam though, the centre lost strategic importance in favour of the two places that mattered, the Red River delta and the Mekong delta. Close to these two regions lay two cities that were destined to dominate the country, demographically, Hanoi and Saigon respectively. This is also why “the centre” was gathered in such a big province by the French: compared to Hanoi and Saigon, and surroundings, it didn’t matter that much anymore. To this day the economic imbalance within the country’s geography is pretty obvious.

Orphans of a King and with not much of a Mandate of Heaven to cling to, for Vietnamese nationalists, the sky was the limit4.

Due to a series of bizarre coincidences, the man who later became known as Ho Chi Minh, and his buddies, were all from what is known as North Central Vietnam5. Forgotten by Hanoi and too far from anywhere that matters, it’s not a surprise that the preachings resonated in what was still a largely rural society.

There’s a whole irony about this that parallels Vingroup-branded electric buses parading around Hanoi. Nguyen Sinh Cung, then at some point Nguyen Ai Quoc, then later Ho Chi Minh, a man of many names, spent a fair amount of time in France, spoke perfect French (and Russian, and Mandarin, etc.). He was educated by the French, and unlike Soviet revolutionaries, whose revolution was born out of the utopia of a fully industrialised world where progress was king, Ho’s mantra was that of elevating the peasant class by educating them. Of course it’s ridiculous to claim that “you need to be an uneducated peasant to want to educate peasants” but just like branded big-corp buses have a different feel when they stroll around hammer-and-sickle flags, the “homebrew revolutionary” persona does clash a bit with someone who was essentially a result of French colonialism.

There is a lot of controversy about this issue, but the colonisation of Vietnam happened around the same time as Japan’s annexation of Korea (1910). Japan heavily industrialised Korea, while France did not do the same job in Vietnam. Some people in the Vietnamese opposition believe that Vietnam could have been like South Korea had it not become communist, but it lacked a whole productive sector that the Korean peninsula acquired – and this is also the reason why, for instance, post-war North Korea was relatively fine.

Therefore, there was no other branding choice for Ho. Underdeveloped lands and illiterate people, the peasant class had to revolt.

Literacy was also an interesting point on another aspect. The French colonial system had retrieved from the freezers of history a book called Dictionarium Annamiticum (Annam strikes again) written by a jesuit missionary in the 1650s, Alexandre de Rhodes, which together with all the words it collected it also conveniently contained a pretty well made transliteration into latin letters of the Vietnamese language. It wasn’t a one person job and the original inventors of the latin transliteration of the Vietnamese language were jesuit missionaries, but why not bring the spotlight on the one French person, if we have that chance?

Latinisation was also seen as a way to wring Vietnam away from the influence of its cultural daddy China, and of course the nationalist force took great advantage of it. Like in many other places around the same era, alphabetisation introduced a form of political ideology. You are Vietnamese, and these are your letters – it’s called chu quoc ngu, “the national alphabet” not “latin” or anything.

Once the land adopted the new script, the previous writing system based on Chinese characters was abandoned. It is true that almost nobody could read it, and its very existence was tied to the knowledge of Chinese – unlike, say, Japan, where the vast majority of the literate population doesn’t actually know Chinese – but severing the ties explicitly sent a message.

The other message was the stroke of pen in which the national alphabet and language acquired significance in a fragmented country: no other language or script is accepted, and, with the exception of religious sites, this is still the case.

Does this sound very communist or “socialist-internationalist”? Not particularly. It does, ironically, sound very, very French.

The South

The south was also very far from Tonkin and the traditional ancestral lands of the Vietnamese people, but let’s not make the mistake of thinking that a Champa revival was in the agenda. Nevertheless, the traditional borders of Champa coincide almost exactly with the borders of South Vietnam, and this isn’t an eerie coincidence.

With some anachronism we regard Saigon as a French creation (it is, kind of) and South Vietnam as an exclusively western creation but we forget that the Republic of Vietnam and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam6 had at their core an ideological and a cultural and, in away, ancestral split that was represented in big parts of the population.

The Viet Minh, the communist revolutionary army, was the strongest militia available. Ho Chi Minh was the most charismatic leader of the nationalist front. These two facts alone contribute to the theory that North Vietnam wasn’t Vietnam fighting Vietnam. It was Vietnam fighting the Americans.

We forget though that plenty of Southern-leaders-to-be started their military careers in the Viet Minh when joining a communist militia was about fighting for independence and exploitation and it had less of an ideological charge. Two such examples were Nguyen Khanh7 and Nguyen Van Thieu8.

On the other hand, many Southern Vietnamese leaders who didn’t join the Viet Minh and were part of other nationalist organisations, received a fairly orthodox formal French education, just like Ho Chi Minh. Such examples are Ngo Dinh Diem9 and Duong Van Minh10. The case of Ngo Dinh Diem is quite emblematic because coming from a Catholic family he suffered persecution in his youth, as was common against Christians in Confucian Asia, and formed his own personal (Catholic) militia whose main goal was also to get rid of the French11.

The stronger Christian presence added to the mess of the South’s identity crisis12. But there were other details that made everything more complicated, especially later when the nationalist and communist ideologies rose to prominence.

One was that Saigon was essentially born as a glorified trading post. It wasn’t an imperial capital with fancy ruins, it wasn’t a holy land with pilgrimage sites, it wasn’t ancient, it wasn’t attractive. It was a place where people of all places, east and west, started going there to do business.

The other, which isn’t unheard of in South East Asia, was that Saigon attracted the lion’s share of the ethnic Chinese immigrants that settled in Vietnam.

These things put together sort of intertwine with the palace intrigues at the court of the Republic of Vietnam, where backstabbing and infighting were national pastimes. And all of this contrasts severely with the counterpart. There was close to no infighting, the ideological leadership was clear, as were political, diplomatic and military leadership.

How the French actually got kicked out was sort of straightforward. Armies organise, governments get unpopular, and at some point there is a military confrontation, one of the two sides loses, and since this happened in 1954, after the Second World War, it pushed France to give up the entirety of Indochina, and eventually original power was restored in Cambodia and Laos …

… But Not in Vietnam

It’s extremely tempting to start talking about the Vietnam War at this point, but then if you reached this far into this piece you will be bored to death.

Yes, the Viet Minh were promised unity and got half of the country instead. The Northern Half. They got mad and together with their buddies from the South, the Viet Cong13 they embarked on a long journey to “liberate” the whole country from “the west”, which caused long lasting damage to the land and between 1.5 and 3.5 million dead, in a country that in 1975 had less than 50 million.

But again, the South wasn’t just a puppet state, and the people fighting for the South were not just France or America’s useful idiots.

And it wasn’t even just “the South” that fought against the North Vietnamese Army. One example of extremely unlucky population was the Hmong, that sandwiched between Northern Laos and North Vietnam placed a very unlucky geopolitical bet. Just like Finland in the Second World War but without its weight in terms of population, they conveniently allied themselves with the losing-side-to-be. The aftermath was a massive eviction of Hmong people from their lands, who then, as a token of gratitude, were allowed to resettle in the US.

This bet wasn’t irrational or even ideological at all. The Hmong had gambled for potential statehood or even just autonomy in a future slightly differently shaped region. This isn’t to say that royalist Laos and South Vietnam were friendlier than North Vietnam to different ethnic groups – they were very similar – rather, the Hmong were certain that there was no place for them within North Vietnam’s plan, and they thought their chances were higher in a particular camp, just like Finland sided against its historical enemy, Russia, rather than “with” Nazi Germany.

The example of the Hmong in particular is a sign of how much more of a stronger ideology nationalism was, rather than communism or hostility to the west. The Hmong and the Vietnamese (and/or Lao in that case) were two opposing forces that could not be reconciled because at the end of the day the Hmong wanted to be Hmong more than they wanted to be Vietnamese.

In the end the real war was between a disorganised and corrupt sequence of leaders who spent a fair amount of time killing each other, and an extremely organised political system born out of “the” independence militia. This gave North Vietnam both street cred among the population, and political legitimacy in general, as their existence was primarily a wish of “the Vietnamese people” rather than external forces14.

This is where we need to once again state the obvious, which isn’t that obvious after all. The goal of the Viet Minh wasn’t to make a communist country. It was to make a Vietnamese country where they were in charge their own way. Conveniently, the fragmented South was puppeteered by the West, which gave even more legitimacy to the Viet Minh’s ideology.

Renewal

Let’s not be dishonest. Communism was probably a driving force of it all. But it’s impossible to know how much it would have been, or remained so after the end of French Indochina, had western powers not interfered.

At some point Soviet influence waned, and with strained relations with China, from an outsider’s perspective, we could see that keeping ideological consistency with the eastern bloc wasn’t a requirement. There’s something else to keep in mind. Unlike China, Vietnam had been placed under severe sanctions at the foundational part of its modern history, as relations with the US got normalised only in the 1990s (twenty years after China). This is what bitterness from losing a war leads to.

Twenty years of war made Vietnam extremely conservative and reluctant to change. There’s also the factor that dropping the mask – a mask that stands to this day – would mean accepting ideological defeat of the original liberation mission. It would also open Pandora’s Box of actually inspecting the country’s idols, reviewing history and potentially fracturing the country once again, or even tearing it apart, as realising that the foundational ground on which is stands, which is painted on the walls of most cities, and taught to every citizen from childhood until their death, is not so solid after all.

None of this prevents incremental change though, and indeed it arrived. Just like in China, the socialist market economy machine created in the 1980s started reaping very precious fruit a couple of decades later, bringing a shocking amount of people out of poverty. Part of this happened through a massive industrialisation campaign, something that, as mentioned before, the previous colonial overlords (and the subsequent governments between wars and sanctions) “forgot” to do. Was this a U-turn from the peasant revolution? Or was the peasant revolution just the nationalist struggle’s means to an end with whichever resources they had at hand? Most definitely the latter.

The “renewal” (Doi Moi) movement of Vietnam of the 1980s therefore started at a time when Vietnam was still isolated. We can’t know if modernisation could have started earlier, and we can’t know if less antagonism during the Cold War would have turned Vietnam into a place like Poland where the ideology on the ground was vastly different from the State’s.

What we do know is that Ho Chi Minh himself, being outside-facing as he was, would not have wished for his country to be isolated, and this was the same as most other contemporary nationalist leaders15.

Western authors regard renovation in post-revolutionary states as something that happens “despite” the original goal. This is only true if we stick to the orthodoxy of Vietnam’s nation building wrapped around communism. It’s the other way round. Communism was part of the nation building, and, again, the ends justify the means. What we see today isn’t in contradiction with the peasant revolution. It’s a consequence.

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam today uses a funny expression to talk about its foreign policy, bamboo diplomacy (ngoai giao cay tre, literally “diplomacy of the bamboo tree”). It roughly means to bend as much as you can so that none of your actions piss off the regional bullies.

The State ideology, as we’ve seen, has been incredibly flexible too. Growth has happened very unequally, but it has happened, and noticeably so. But the most ironic aspect of the inequalities within Vietnam is that the people who were in theory the worst ideological enemies of the Viet Minh16 are the people why benefitted the most from the economic growth, and especially this ideological flexibility. The corporations, the factory owners, and even many individuals in all the ranks of the political apparatus who routinely manage to rake in amounts of money which would make the average western politician very jealous. Perhaps the fact that being “close to the system” brings fortune is one of the few things that Vietnam has in common with the communist societies of the past.

People who have been less lucky probably find motivation in the fact that the new generation of their offspring will make it. Unfortunately, unless tackling inequalities becomes a priority, chances for those who got left behind will remain pretty slim. Sooner or later, when it’ll become obvious that redistribution, bizarrely, has never been a priority for the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, those people will probably ask for the bill.

- Peninsular Malaysia is also technically a regional power but their projection is far more to the south, far from the “important” areas of Thailand and Burma. Their inclusion in South East Asia is similar to Portugal’s inclusion in Western Europe, which is more geographical than it is economic or social.

- Thailand is a little miracle and deserves a discussion of its own as a country that has managed to juggle its own independence by pitting France and England against each other and making some slight territorial concessions. The result was a massive head start in the race for development, and it is the main reason why people “go to Thailand” instead of other countries.

- In Laos all the kings are recognised as part of the country’s history, except for the latest one. During the civil war, as a desperate attempt to cling to power against the Pathet Lao, the Communist Party helped by North Vietnam first and Vietnam later, he allowed the most brutal bombing campaign ever, in the entire history of the world within the borders of its own country, perpetrated by the US Air Force. After Pathet Lao’s victory, he and his whole family got sent to a concentration camp. They all died there.

- Setting aside Thailand and Cambodia whose kings were always quite strong and beloved, even communist Laos holds a tighter cultural-religious embrace for the population than Vietnam. Even though Laos is much more multicultural, it’s also much more Buddhist.

- North Central Vietnam goes from Thanh Hoa to Danang, at the time called Tourane, but traditionally excluding Danang itself.

- The names are very close to the official names of South and North Korea.

- One of the key figures in the junta that ruled South Vietnam between 1963 and 1967.

- Second President of South Vietnam, from 1967 to 1975.

- First President of South Vietnam, from 1955, the year after the French left, until 1963, when he got deposed.

- He had prominent roles in South Vietnam for two decades but is mostly remembered for being the formal President for two days in April 1975, after effectively being handed the job over by Nguyen Van Thieu. His only duty was surrendering to the North Vietnamese army after the fall of Saigon.

- The irony is that as president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem is remembred as a persecutor of Buddhists, events embodied in the person of Thich Quang Duc, the monk who set himself on fire in 1963 to protest against Ngo Dinh Diem’s rule. He was deposed and assassinated the same year. And, ironically, among the participants in the coup there were the aforementioned former Viet Minh member Nguyen Khanh, and, in a much more prominent role, the aforementioned Duong Van Minh.

- Vung Tau, the main port city in the South, is a unique example in which two big statues of Jesus and Buddha fight for prominence in the city skyline.

- The reason why in the west Viet Cong is thought as the army of North Vietnam is that those were the vietnamese soldiers that the Americans and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam were fighting against, i.e. the communist army in the South. They were allied to, but not the same as, the North Vietnamese Army.

- As stated over and over, this is an oversimplification. The North was supported by the Eastern bloc, but the Viet Minh were born organically, and in the end so was the state of North Vietnam. The Republic of Vietnam had real people and real ideas but it’s undeniable that without Western support it wouldn’t have been born in the first place. This is in massive contrast with, say, North Korea, where Kim Il Sung was essentially handed over to the country as “leader” by the Soviet Union, after having served in the Red Army.

- Mustafa Kemal’s most known motto was “peace at home, peace in the world”, a meaningless sentence that at the very least shows that the nationalist project of the Republic of Turkey was not isolation.

- If we accept that the primary ideology was communism, rather than nationalism.